On 23 January 1691, the Count of Galvez (as in Galveston) appointed Domingo Terán de los Ríos to serve as the first governor of the Spanish province of Coahuila y Texas. Here’s his story:

On 23 January 1691, the Count of Galvez (as in Galveston) appointed Domingo Terán de los Ríos to serve as the first governor of the Spanish province of Coahuila y Texas. Here’s his story:

Six years earlier, pirates captured one of four ships belonging to the French explorer La Salle. When Spanish ships later apprehended these pirates, Mexico’s Viceroy learned of France’s attempt to stake a claim in Texas. He sent General Alonso De Leon to search for the French invaders and wrote a letter to the king of Spain to report the incident and request orders.

It was four years before De Leon discovered the charred ruins of Fort St. Louis on Carcitas Creek. Though the French threat died with the colonists, General De Leon and his accompanying priest, Father Damein Massanet, reasoned that it would be wise to establish a mission among the Caddo Indians in East Texas to reinforce the border with Louisiana. Mission San Francisco de los Tejas was founded before they returned to report to the Viceroy in Mexico City.

By this time, the king’s reply had come from Spain. It was the king’s wish that eight missions be established in East Texas and forts built to guard them. Officially referring to the lands above the Rio Grande as the “Province of the Tejas,” he urged that Domingo Terán be appointed governor of the new province. On 23 January 1691, the Count of Galvez appointed Domingo Terán de los Ríos to serve as the first governor of the Spanish province of Coahuila y Texas.

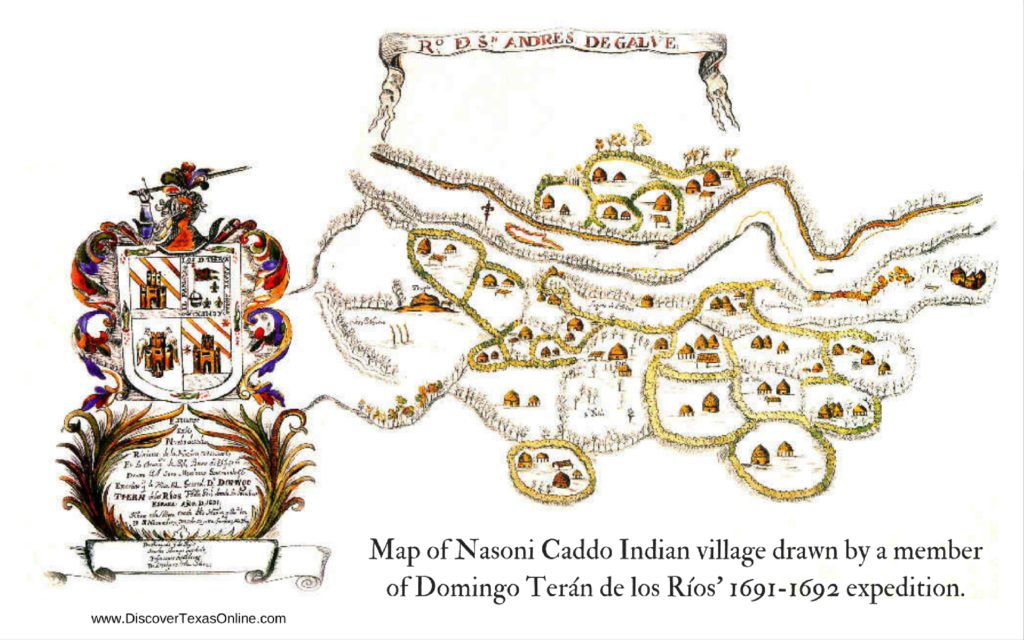

An infantry officer and governor with twenty years’ experience, Terán ably led his small army from a base camp in Monclova on May 16, 1691. In addition to building the missions, his orders were to find the most direct route and name the rivers along the way, keep a diary detailing the land and cultures he encountered, establish friendly relations with the Tejas, and gather information about any European “invaders” and take them captive.

Though Terán was military leader, Padre Massanet was to be a partner in all decisions and had complete control of the supplies. This led to many difficulties. Indians stole their horses while they camped along the Guadalupe River. Here they also received a letter from Mission San Francisco de Los Tejas telling of a smallpox epidemic. The Indians were abandoning the mission in large numbers, taking critical supplies with them. Naturally, Padre Massanet was anxious to reach the mission at top speed, but with their own supplies critically low, Terán thought it best to rendezvous first with supply ships at Matagorda Bay.

His troops were delayed, unable to locate the ships, but they did rescue two French boys who had survived the massacre at Fort St. Louis. They left a letter with the Indians telling the ship’s captain that they were returning to Terán’s camp on the Colorado River. Terán argued that they should make another attempt to find the ships, but Padre Massanet refused to wait. Terán escorted him to the mission before returning to the site of abandoned Fort St. Louis.

There at last he found two supply ships, but they also brought new orders to explore the region he had just left. Terán was tired and ready to go home. A hard march back to the missions found the friars just as discouraged. Wearily, they explored the Neches and Red Rivers looking for a navigable route. The weather was so bitterly cold that nearly all their horses died. Terán could not return to Mexico without horses or supplies. Padre Massanet refused to share the mission’s provisions. Finally Terán took what he needed and left. Six friars went with him, leaving only three missionaries with nine soldiers to guard them.

Another hard, cold march brought them back to Matagorda Bay three months later. Here they met the promised supply ships. While they rested and regained their strength, Terán penned his discouraging report. He felt that he had failed his orders at almost every point, and he was ready to go home. He was so spent, in fact, that he sent his men back by land while he boarded the vessels for Veracruz. Even this proved to be a frustration, though, as the captain had been ordered to explore the Mississippi River before returning. After sailing east for a few days, they ran into bad weather, which forced them to turn back. Terán was going home at last.

Though Terán believed that he had failed, he had actually succeeded in many ways.

- Terán was more than just Texas’ first governor. He was the first government official in Texas–the beginning of recognition of Texas as a political entity.

- He blazed El Camino Real (the King’s Highway) for 1000 miles from Saltillo, Mexico through San Antonio to the Louisiana territory. This route has been extremely important throughout Texas history and is still visible along Highway 21 to this day.

- He named many of Texas’ rivers. Some, like the San Antonio River, later gave their names to modern Texas cities.

- He opened diplomatic conversations with the Caddo.

- His expedition produced the earliest known depiction of a Native Texan community–the map featured above which is preserved in the Archivo General de Indias in Seville, Spain.

This article was taken from Discover Texas/Volume II–Early Texas Explorers. If you are interested in a hands-on history course for your homeschool, homeschool co-op, or parochial school, please explore our website for details!