This week I’d like to talk about timelines and why it’s important to use them.

We don’t talk about timelines much. They’re not “shiny,” I guess, but I think you’ll agree they’re pretty nifty once you see how handy they are as a learning resource.

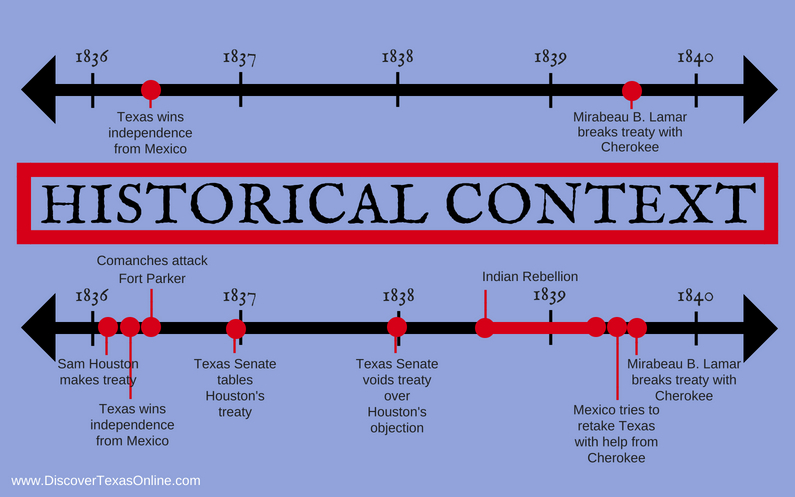

I’ve included one example above. When I first began to learn about the period following the Texas Revolution, all I could really remember was that there were considerable problems with the native Texas tribal people and then Mirabeau B. Lamar (that scoundrel) broke Sam Houston’s treaty with the Cherokee.

But there’s so much more to the story!

In the lower timeline, I’ve filled in some of the blank spaces…and you can see how these tidbits filled in the blank spaces in my understanding as well!

Texas won independence from Mexico at the Battle of San Jacinto (April 21, 1836) after the Mexican dictator, Santa Anna, besieged the Alamo (February 24-March 6). Any good Texan knows that. BUT just ONE DAY before Santa Anna began his attack on the Alamo, Sam Houston was signing a treaty with the Cherokee on February 23, 1836. If you ever wondered why he was a little late pulling the Texas Army together in Gonzales, remember that he was only appointed General of the Texas Army in November 1835, and he’d been plenty busy elsewhere! The Cherokee were apprehensive about how the rebellion in Texas might affect their tribe, and there was no one better suited to speak with them than Sam Houston who, from the age of 16, lived among the Cherokee for several years, was adopted into the tribe, and spoke their language fluently. So for a number of reasons, this treaty–which until recently I knew little about–was a key event.

ALSO the same week we signed the Treaty of Velasco, making Texas independence official, the Comanche and Kiowa tribes attacked a family outpost, Fort Parker, brutally murdering several family members and carrying off little Cynthia Ann Parker. The effect on the public in that day was similar to the effects of domestic terrorism in our time. Texans who had so recently been scared of the encroaching Mexican army were now terrified of violence from another quarter.

The Comanche and the Kiowa who had attacked peaceful Texas families were completely separate tribes from the Cherokee with whom we had a pending treaty, but the brand new Texas Senate felt the need to be careful in setting precedents and establishing public confidence, so instead of ratifying Houston’s treaty with the Cherokee, they tabled the matter to look into it further.

The next year, over then President Houston’s forceful objections, the Senate declared the treaty void. (That means, “No. Unh-uh. We ain’t doin’ that.”)

The Cherokee, understandably, took offense. They had been patient, but now felt they had been betrayed. Unrest and uprisings began again, which did little to convince Texans that the tribes could be trusted.

Then in May 1839 the Texas Rangers captured a Mexican rebel, Manuel Flores, trying to infiltrate the new republic with the goal of retaking Texas for Mexico by force. He was carrying letters that seemed to indicate that Mexico had made an agreement with the Cherokee to stir up trouble.

This was kerosene to a fire already kindled! Sam Houston was out of office by this time, and Mirabeau B. Lamar was president of Texas. Lamar never did like Houston, and he decided he didn’t like Houston’s friends or Houston’s treaty, either. In July 1839, he began to round up all the Cherokee–and pretty much all the other indigenous people–to expel them from Texas by force…and he wasn’t too particular about how he did it. (Like I say, he was a scoundrel.)

See how much more interesting the picture becomes when you add more pieces, more color, and different perspectives?

History is all about which questions you ask.

Timelines help us remember to ask, “Now, why did they do that?”