Emily West is one of my favorite heroines of Texas History, and it’s fitting that I should mention her not only during Black History Month, but also on Valentine’s Day because the lyrics of the famous song, The Yellow Rose of Texas, describe her as “the sweetest little rosebud that Texas even knew.”

But who was she?

If nothing else, she is a good example of why I am a stickler for original source documents–first-hand eye-witness accounts of historical events. But there is MUCH more to tell about this brave lady.

Let’s look at what we know about Emily West. It’s not much. Keep in mind that most women lived very private lives before the 20th century. A lady might be mentioned in print only upon the occasions of her birth, her marriage, and her death. In the case of a lady of color, I’m fairly sure there was usually even less reported about her. So to have two original source documents which mention Emily West and a third hearsay account within her lifetime is perhaps unusual only because we have even this much.

We must also keep in mind the social and political conventions of the day. Slavery was legal in the United States in 1836. In fact, it was illegal in some southern states to free slaves, but in the northern states abolitionist sentiments were already growing. Under Mexican law, settlers were forbidden to bring slaves from the United States (though a loophole allowed them to bring slaves from elsewhere). To get around this law, some American slave owners immigrating to Texas listed their slaves as “employees” or “indentured servants”. In the case of Emily West, this causes some confusion.

We do not know when Emily West was born, but we do know that she was born a free Black in New Haven, Connecticut. The 1830 census suggests she may have lived there in the household of Simeon Jocelyn, a noted anti-slavery philanthropist who had earlier helped arrange the defense of the Amistad captives. If this was Emily, she is listed in the 1830 census only as a “free colored female between the ages of 10-24.” It’s not much to go on, but even this is still important background because the first document to mention Emily West by name is a contract dated October 1835 in which Col. James Morgan, a New York businessman bound for Texas, hires one Emily D. West as a housekeeper in his New Washington hotel.

This agreement, made & entered into by and between Emily West of New Haven, Conn. of the one part & James Morgan of Texas of the other part, Witnesseth that the said West, hereby binds herself that she will go out in said Morgan’s Vessel to Texas and there work for said Morgan at any kind of house work she, said West is qualified to do and to industriously pursue the same from the time she commences until the end of twelve months and not to quit or leave said Morgan’s employ after she commences work for him, at any time whatever, without said Morgan’s consent, until the end of twelve months aforesaid, said Morgan hereby binding himself to the said West out to Texas, on board said Morgan’s vessel, free of expense, and to set said West to work within one week after she gets there if not sooner, said Morgan agreeing to pay said West at the rate of one hundred dollars pr. year, said Wages to be paid every three months if required.

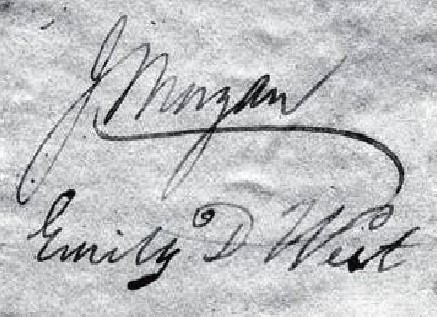

In witness thereof the parties have hereunto set their hands and seal in New York this “5th day of October 1835. In the presence of Frederick Platt, Simeon L. Jacilyn, J Morgan Emily D West.

Note two things:

- The signatures of J Morgan and Emily D West (seen above) indicate that Emily was literate. In fact, she had lovely penmanship.

- The contract was witnessed by Simeon Jocelyn, which may support the suspicion that she was the “free colored female” who lived in his household in 1830 and would also indicate that this contract was not simply a ruse to disguise the import of a contraband slave or servant indentured against her will. If Mr. Jocelyn was involved, this was likely a bona fide contract of employment. Her wages of approximately 30 cents/day were comparable with other women of her era.

On April 16, 1836, while James Morgan was in Galveston commanding Fort Travis, Mexican cavalrymen under command of Col. Juan Almonte marched into New Washington hoping to seize President David G. Burnet. The president, however, was already aboard a schooner bound for Galveston Island. As the president and his family sailed away, the troops seized Emily and other black servants at Morgan’s warehouse, along with a number of white residents and workmen. Gen. Santa Anna arrived at New Washington the following day, and after three days of resting and looting the warehouses, he ordered the buildings set ablaze and left in pursuit of Sam Houston’s army, which was encamped about ten miles away on Buffalo Bayou. As a captive, Emily would have been forced to accompany the Mexican army.

A second archival document, an undated letter Isaac N. Moreland wrote on behalf of Emily D. West sometime after April 1836 but before 1842, sheds light on what happened next:

Capitol, Thursday Morning

To the Hon. Dr. Irion

The bearer of this-Emily D. West has been since my first acquaintance with her, in April of –36 a free woman—she Emigrated to this Country with Col. Ja’s Morgan from the state of N. York in september of 35 and is now anxious to return and wishes a passport—I believe myself, that she is entitled to one and has requested me to give her this note to you.

Your Obd’t Serv’t

I.N. Moreland

Her free papers were Lost at San Jacinto as I am Informed and believe in April of –36

Moreland

Isaac N. Moreland served on the battlefield of San Jacinto as an artillery captain. In Spring 1837 he was practicing law with David B. Burnet in Houston, and he served as Chief Justice of the Second Judicial District (Harrisburg County) under President Lamar until his death [on June 9,] 1842. If Emily West was captured by Santa Anna and dragged along to San Jacinto, it is very possible that this is how Capt. Moreland came to meet her and know that “her free papers were lost at San Jacinto” in April of 1836.

This letter is also interesting due to a later connection.

The first person to suggest the notion that the actions of one woman influenced the Texians’ victory at San Jacinto was an English traveller, William Bollaert. Arriving in Galveston in 1842, Bollaert toured the Republic of Texas for two years. On July 7, 1842, Bollaert scribbled in his diary:

The battle of San Jacinto was probably lost to the Mexicans owing to the influence of a mulatta [sic] girl belonging to Colonel [James] Morgan who was closeted in the tent with G’l Santana [sic] at the time when the cry was made, ‘The enemy! They come! They come!’ and detained Santana so long that order could not be restored again.

By some accounts, the name “Emily” was later jotted in the margin of this diary entry. We have already established that Emily did not “belong” to Col. Morgan, but Bollaert’s account led some readers to assume that Emily would have taken the surname of Morgan as many slaves did, though there is no indication that this is true.

According to James E. Crisp, professor of History at North Carolina State University, his student James Lutzweiler discovered the key to the connection while researching Bollaert’s manuscripts for his Master’s Thesis. None other than Sam Houston told Bollaert this story just weeks after visiting Isaac Moreland on his deathbed. Letters from Houston to his wife confirm his visit with Moreland and that Houston later spoke at his funeral. Could it be that when they met after the battle, Emily related the tale to Moreland who then told it to Houston who told it to Bollaert?

As for Emily being “the Yellow Rose of Texas”, that song does not appear until 1853 when it was first published by a black-face minstrel act called the Christy’s Minstrels. The song regained popularity a century later, sung by Roy Rogers in the 1944 movie western, The Yellow Rose of Texas.

It wasn’t until the 1960s that we find journalists making bawdy claims that Emily West was the “deliberately provacative” “Yellow Rose” who “gave her all for Texas, piece by piece.”

For this there is not one shred of evidence.

Contrary to the sensational fabrication presented in a few recent revisionist tall tales:

- Emily West was never at the Alamo.

- She was not among the survivors sent to Gonzales who reported to Houston.

- There is no record that she had a brother named Jupiter.

- While we know that one free man of color died defending the Alamo, his name was John.

- If Emily West was in Santa Anna’s tent when the Texans charged the Mexican camp on April 21, it was almost certainly not by her choice or consent.

- There is no indication that she had ever met Sam Houston, so she could not possibly have known his plans.

False “popularist” depictions of Emily West do her a grave injustice, whether intended or not, and are rather an insult to the real Emily West. Life was surely difficult enough for a biracial woman in 1836 without having writers assault her good character to create a bit of titillating drama.