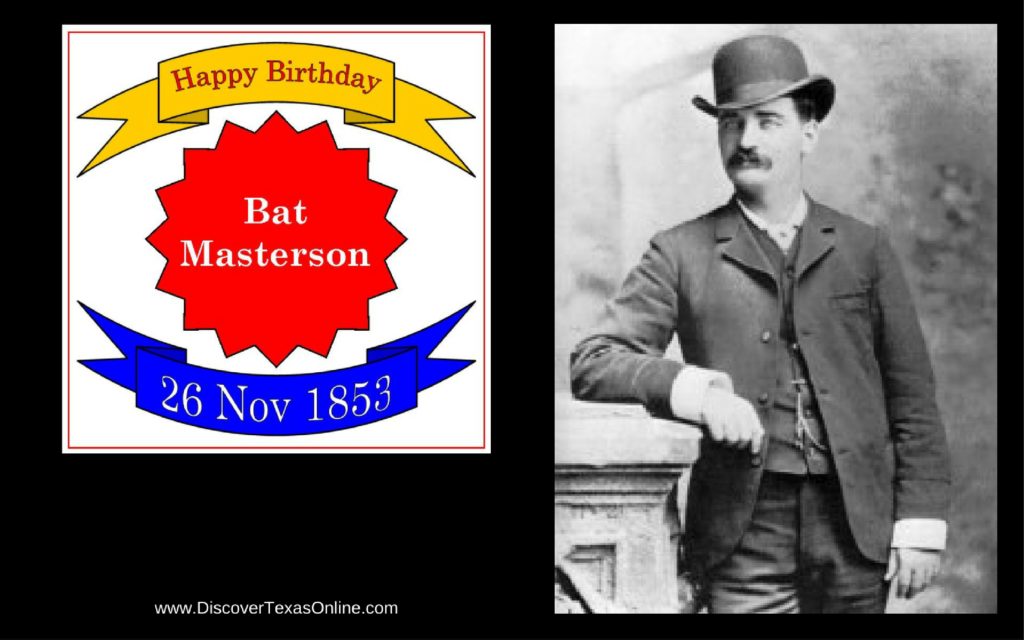

Bat Masterson was born in Canada on November 26, 1853. So what’s he doing in a line-up of famous Texans?

Bat’s parents were of Irish stock–his mother an immigrant–and they moved their large and growing family around a lot, farming first in Quebec, then New York, Illinois, and finally settling near Wichita, Kansas.

You know what they say about “#2 tries harder”–Bat was the second of seven, and you might get the idea that he learned to stand his ground and state his ‘druthers rather early. His parents had him baptized as “Bartholomew” (hence “Bat”), but he later called himself William Barclay Masterson. Kansas, in the days of the westward expansion, was part of the “Wild West.” When he was 19, Bat and his brother Ed were hired to grade a 5-mile section of track for the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad. They did the work, but their employer disappeared without paying them. It took Bat the better part of a year to track the man down, but when he caught up with him on a train, he marched him onto the rear platform and demanded his money at gunpoint. His cheating boss forked over $300–all that he owed Bat, Ed, and their friend–to the cheers of a large crowd that had gathered to watch.

Bat had gained a reputation as a buffalo hunter while still in his teens, and that’s what eventually brought him to Texas. In June of 1874 he stopped at the trading post at Adobe Walls in the Texas Panhandle. On the night of June 26 he and about 28 others were sleeping in and around James Hanrahan’s saloon and the two stores nearby. Hanrahan had just returned from Dodge City where he’d encountered a large band of troublesome Cheyenne and heard rumors of a war party. Because Adobe Walls was isolated and had been the repeated target of Indian attacks, Hanrahan was on the alert. He had no intention of becoming a victim of an attack, but neither did he want to scare off his customers. What to do? Hanrahan kept watch through the night. Some say it was a well-timed coincidence that the ridge pole of the structure cracked loudly at 2 in the morning the night a large party of Comanche, Cheyenne, and Kiowa warriors moved into position near the trading post. Some say Hanrahan heard their approach and hit the ridge pole himself. Either way, the crack sounded like the report of a rifle, and the men sleeping in Hanrahan’s saloon were instantly awake and alert.

Billy Dixon, another of the patrons at Hanrahan’s that night, gave this account:

There was never a more splendidly barbaric sight. In after years I was glad that I had seen it. Hundreds of warriors, the flower of the fighting men of the southwestern Plains tribes, mounted upon their finest horses, armed with guns and lances, and carrying heavy shields of thick buffalo hide, were coming like the wind. Over all was splashed the rich colors of red, vermillion and ochre, on the bodies of the men, on the bodies of the running horses. Scalps dangled from bridles, gorgeous war-bonnets fluttered their plumes, bright feathers dangled from the tails and manes of the horses, and the bronzed, halfnaked bodies of the riders glittered with ornaments of silver and brass. Behind this headlong charging host stretched the Plains, on whose horizon the rising sun was lifting its morning fires. The warriors seemed to emerge from this glowing background. [from The Life of Billy Dixon]

Over 700 warriors led by Comanche Chief Quanah Parker believed their medicine man Isatai’i when he told them that special paint on their bodies would protect them from the white men’s bullets. During the initial attack, the Indian warriors killed three men who were caught outside and rode close enough to pound on the doors and windows of the buildings. The hunters in Hanrahan’s saloon turned back the attack, killing at least 15 of the Indian warriors. While this was a small number out of 700, the deaths were demoralizing because they disproved Isatai’i’s guarantee of protection. The Indians rode out of range to decide what to do, besieging the little cluster of buildings.

The siege and skirmishing lasted five days, and we might imagine that the men compared and boasted about their shooting skills to lighten the mood. Finally Bat Masterson challenged Billy Dixon, who had a reputation for being a crack shot, to shoot one of the Indians who sat on horseback, watching, nearly a mile away. Bat even passed around his legendary bowler hat to take up a collection.

Dixon took aim with a “Big Fifty” Sharps rifle he borrowed from Hanrahan and fired. Even he was astonished when, seconds later, a warrior fell from his horse–dead. The Indians were so unnerved that they gave up the fight and went home.

Bat Masterson survived the battle and went on to live a rather legendary life as a civilian scout for the U.S. Army, a gunfighter and marshal in Dodge City, Kansas, a gambler, a leading authority on prizefighting, a reporter and columnist for the New York Morning Telegraph, and a close friend of both Wyatt Earp and President Teddy Roosevelt (with whom, I believe, he had much in common).

Men like Masterson, Dixon, and Roosevelt lived during a fascinating time of transition. They saw the West won, the Great Plains fenced, and the modern era emerge as America spread from sea to shining sea.