Let me start by saying that I had fewer complaints about this episode than any of the others. There were some bits of history that the producers did very well to bring out, but there were other aspects–some rather important–where the folks in Hollywood took unnecessary liberties concerning what really happened at the Battle of San Jacinto.

Let’s begin with a brief recap:

Houston began with approximately 1200 Texians in his volunteer army, but after the slaughter at the Alamo and the Goliad massacre, approximately 400 deserted him to get their families to safety in the runaway scrape. He might have hoped for a larger force, but this number represents 2%-3% of Texas population of 38,500 in 1836, which is only a little less that the proportion who normally serve in a country’s military. There are many theories about why Houston prolonged his retreat, but it is a fact that this tactic caused dissension. Texas President David Burnet did order Houston to stop his retreat, and Secretary of War Thomas Rusk urged him to take decisive action. The Texas Rising mini-series scored a win for conveying this conflict.

The “Twin Sisters”–a pair of cannons presented to the Texas rebels by the citizens of Ohio–did give the Texian army a heavy artillery advantage over the Mexicans, who had only one cannon. Since the United States maintained a position of neutrality in Texas’ fight with Mexico, the guns were shipped as “hollow ware”. 😉 An agent of the Republic of Texas officially received the guns in New Orleans on March 16, 1836 and placed them on the schooner Pennsylvania, bound for Galveston Island. Also aboard was Dr. Charles Rice and his family, who were moving to Texas. The schooner arrived in Galveston in early April, and the cannons were presented to representatives of Texas by Dr. Rice’s twin daughters, Elizabeth and Eleanor. Someone in the crowd remarked that there were “two sets of twins”–the girls and the guns–which is how the cannons came to be nicknamed the Twin Sisters. (Calling them “Daphne and Penelope” as Texas Rising does is likely conjecture. My guess is that “Elizabeth and Eleanor” would have been more likely.) Shall we declare this a draw? The details don’t seem that important. Either way, there was some difficulty in getting them to Sam Houston’s marching army. I find no record of who, exactly, brought them. Could have been Deaf Smith and the Texas Rangers…or not. But they did cross the Brazos on April 11, just in the nick of time.

Santa Anna marched his Mexican Army into Harrisburg (present-day Houston) April 15th and burned it. On April 19th he pursued the retreating Texas provisional government into New Washington (Morgan’s Point) just in time to see Texas President David Burnet setting sail for Galveston. It was here that he captured Emily D. West before ransacking and burning the hotel and warehouses of her employer, James Morgan. In my imagination I can see bravely staying at her post, as she’d given her word to do in her contract, before saving her passport and precious freedom papers from the flames as she and the other captives were dragged along to San Jacinto. I can only wish that the Hollywood script writers had seen fit to show us this very human drama rather than the fabrication they inserted instead. I would call this omission a great loss.

While this was happening, Houston’s volunteers, who had dwindled to about 700-900 by this time, reached the settlement of New Kentucky (near present-day Tomball, Texas) where the road from Washington-on-the-Brazos (not to be confused with New Washington) forked. One route led to safety in Louisiana; the other to the smoldering site of Harrisburg. The “Which Way Tree” stood at the junction, one branch pointing along each route. Here the final decision was made to march toward the smoldering remains of Harrisburg and a decisive confrontation with Santa Anna’s army that was surely certain. The “Which Way Tree” is one of those footnotes of history that I didn’t know about, and I’m truly grateful to have learned about it from this mini-series. Another win for Texas Rising.

On April 20th, the day before the battle, Col. Sidney Sherman did “go off half-cocked” much as depicted in Texas Rising, engaging the enemy against orders and costing the lives of one Texan and several horses. During the skirmish, Private Mirabeau B. Lamar saved the life of Thomas Rusk as well as another soldier. General Houston was so disgusted with Sherman that he removed him from command, granting Lamar a field promotion to the rank of Colonel and putting him in command of the cavalry on the day of battle. Yet another win for Texas Rising.

It’s a small point, but I was impressed that Houston had his men play Come to the Bower as they marched. What can I say? I’m a sucker for historically accurate details. Chalk up another win for Texas Rising (even though the tune was played on that day by Daniel Davis and his son, George Washington Davis, who were FIDDLERS. No fifes or drums in the Texas Army, though there might have been some spoons, bones, or mouth harps as accompaniment). As Houston marched his troops to their battle positions, he requested Come to the Bower because it was a bar ditty rather than a military song. By some accounts, Houston hoped that the lighthearted tune might convince Santa Anna that he was only marching his men out for some much-needed drilling rather than preparing to attack.

…and then the script writers stumbled again and fell from my good graces. 😉

Mexican General Martin Perfecto de Cos was Santa Anna’s brother-in-law (or perhaps his cousin…and, to my way of thinking, arrogance must have been a family trait, but I digress). He marched across Vince’s Bayou on the morning of April 21 with approximately 500 men, bringing the Mexican forces to about 1200-1500 in number. Houston sent a small group led by Deaf Smith to burn the bridge. Since steel-reinforced concrete was not even invented until 1849, Vince’s bridge could not have had concrete piers as depicted in the mini-series. Records also indicate that it was burned, not “blown”, though exploding gunpowder makes for better drama. The important part is that the destruction of the bridge did NOT prevent at least one major group of Mexican reinforcements from arriving, though it’s destruction did cut off the only route for further reinforcements. It also cut off the means of escape and retreat for either army. Once Vince’s Bridge was destroyed, Texas independence would have to be decided at San Jacinto. Once Deaf Smith reported that the bridge was destroyed, Houston decided to launch his attack at 3:30 in the afternoon, during siesta when, for some reason, Santa Anna did not even post look-outs. Houston absolutely did not order his offensive based on the advice of Emily West, a woman he had never met and who could not have known anything about the battle plans. Texas Rising blew more than Vince’s Bridge!

As a writer and as an animal lover I also object to the addition of a scene where Deaf Smith has to shoot his horse. Historically, I find no evidence that it happened, and it added nothing whatsoever to the story line. That bit of pointless fantasy seems to have been an egregious attempt to jerk a few tears out of the viewers.

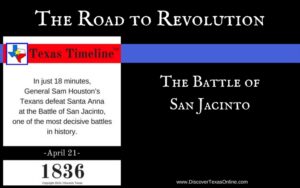

Texas Rising did do a pretty good job, though, of depicting the brevity of the battle–9 1/2 minutes on screen and about 18 minutes in 1836. The Mexican Army saw 630 killed in action, about 200 wounded, and 700 rounded up as prisoners of war. By contrast, the Texians only had 9 killed or mortally wounded with an additional 30 wounded. It was, in short, a stunning victory. And Juan Seguin’s brave Tejano volunteers DID wear playing cards in their hatbands to help the Texians differentiate them from the Mexican soldiers. We’ll call the battle scenes another win for Texas Rising.

Not to be petty, but just because the real story is so interesting–Sam Houston did not ride into battle on a white horse, and he surely did not ride out on one. Original documents tell us that en route to San Jacinto he purchased a horse from Isom Parmer for 400 Mexican silver dollars–a dapple gray with good looks but less luck. Houston led the charge into battle, and the gray was shot dead, perhaps by the same musket ball that shattered Houston’s left ankle. (Despite the famous painting and a good deal of quibbling among historians, a letter from Houston himself as well as a book written by his son specifically mentions the left leg.) General Houston then grabbed the horse of a slain Mexican officer and remounted, but that horse, too, was shot out from under him. (Actually, it fell on top of him. I haven’t been able to find out if it fell on the same leg that was shattered earlier.) At any rate, Houston somehow managed to get free and mounted a third horse, which he rode for the remainder of the 18 minute battle. It was a bad day for horses, and for my part I’m glad Texas Rising did not show it!

Steve Stapp

Nice job, Lynn. 🙂 By the way, what did you think of the job John Lee Hancock did with the movie “The Alamo” that had Billy Bob Thornton playing Davy Crockett?

Lynn Dean

Is that the one Disney did not to long ago? The casting seemed good, but it got only fair-to-middling reviews. To be honest, I haven’t seen it. When I see reviews that say, “A perfect blend of history and Hollywood”, it’s kind of a turn-off. 😛

steve Stapp

Lynn,

Lisa and I both think you should see it. 🙂